Famed American Army general George S. Patton once advised those under his command to “accept the challenges so that you may feel the exhilaration of victory.”

Unlike a military conquest, I’m pretty sure that none of the photography projects that any of us engage in will ever have such profound global implications. Yet, given that any photographer worth his or her camera strap will face challenges within the context of their art, I think General Patton’s words come through as both valuable and relevant.

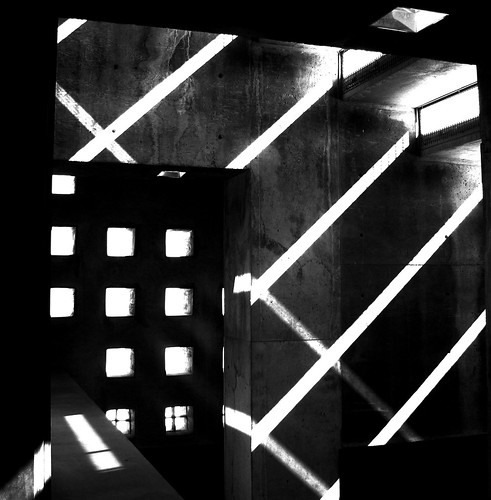

In some instances, we set the challenges for ourselves: to complete a 365 project, to refine our panning technique, to shoot portraits of strangers. Generally speaking, accomplishing these goals simply requires healthy doses of discipline, patience, and courage. Other times, challenges arise as a matter of circumstance; there is no shortage of things that could possibly go wrong or get in the way of getting the perfect shot. One of the obstacles that so often rears its ugly head is that of having to shoot in low light.

Give Me the Light

Available light photography (also referred to as low light photography) really is exactly what it sounds like: taking photographs using nothing but whatever light source is present at the moment (which is why there are some who will argue that shooting in the midday sun also constitutes available light photography; but for the sake of this discussion, I am on the side of those who define available light as low light).

You are bound to find yourself in a situation where the use of flash is prohibited or when you are out and about with just your camera, no extraneous gear; you cannot, in good conscience, pass up a shot due to any manner of external limitation. In fact, I am willing to bet that you will grow to appreciate the allure of available light photography, so long as you stick with it and learn some techniques to help you overcome the trepidation associated with using your camera in less than ideal environments. Thus, I present to those who may be feeling a bit apprehensive, a series of practical tips that you can hopefully call upon the next time a low light photography opportunity presents itself.

- Use a fast lens. A fast lens is one with a larger aperture such as f/1.4; it is important to allow as much light as possible to hit the camera’s sensor and large apertures help accomplish this.

- Use a prime lens. Prime lenses are typically faster than zoom lenses and tend to exhibit less flare, which is a significant consideration when shooting into the light.

- Boost your ISO. Most DSLRs produce great results at ISO 3200 and many can easily do the same at ISO 6400 and higher. Don’t be afraid of a little noise; you can either deal with it in post or…just forget about it. A truly great shot will command attention and no one will even care about the amount of noise present, if they even notice it at all.

- Slow down the shutter. The longer your camera’s shutter is open, the more light it takes in, which is exactly what you want in a setting where good lighting is scarce.

- Use image stabilization. Select lenses have a built-in feature that helps compensate for the blurry effects of hand-holding your camera, particularly at lower shutter speeds. Nikon, Canon, Sigma, and Tamron all make lenses with this feature, while Sony and Pentax have image stabilization built into their camera bodies.

- Shoot in continuous drive mode. When you’re using slow shutter speeds, the act of pressing and releasing the shutter is one of the culprits of camera shake. Continuous drive mode allows you to capture a continuous series of shots as long as you are holding down the shutter button; firing off multiple shots will increase the likelihood that at least one of them is sharp and in focus.

- Go towards the light. It sounds fairly obvious, but do your best to seek out the best lighting possible, whether that’s under a streetlight or next to a store window. Maximize the assets your environment provides for you.

- Wait for the right moment. If you are out shooting candids at night, you may find it effective to wait until your subject remains still. That stillness will likely be fleeting, so be vigilant and get your shot.

- Embrace the blur. There is no reason to think that all blur is always a bad thing; you may find that a little blur and the motion it conveys enhances the creative aesthetic of your low light photos.

Hey, You Forgot to Mention Tripods

Well, no I didn’t forget; I purposely excluded the use of a tripod. The goal here is to invoke the mantra of Henri Cartier-Bresson: capture “the decisive moment.” More often than not, a tripod will only add to the impediments acting to slow you down and make the whole process more difficult than it needs to be. Plus, there are venues that have a strict policy prohibiting the use of tripods. Sporting events and museums are a couple of common examples.

There won’t be any such regulations in effect preventing you from using a tripod when you’re out on the street shooting candids, but I can’t imagine that you would actually want to go through the inconvenience of lugging it around and setting it up. Poor lighting aside, a tripod would probably be a more substantial hindrance to shooting “on the fly” than anything else.

However, if there is some random item or structure around that can serve to stabilize your camera, by all means use it. Again, look to make the most of all the tools you can find in your current shooting environment. You can use what’s there and when you’re ready to move on, you don’t have to pack up and haul anything.

Available light photography differentiates itself from other genres of photography by emphasizing its naturally intimate charm; it focuses less on the obvious features that would normally be captured by using something like the sunny 16 rule, and instead allows us to peer into the shadows, giving us a somewhat more exotic impression of a subject. This is not to say that available light/low light photography is “better” than any other kind. It’s just different. And it represents a challenge that, once conquered, is certain to leave you with a sense of exhilaration.

3 Comments

It’s always great to be included in these posts. Thanks.

It’s a great shot! 🙂

I need to calm down, wait for the light and shoot