Some may quarrel with me, but I believe that Hungary – especially during the Austro-Hungarian Empire – gave us many of photography’s most titanic figures. I like to write articles in which I speak of photographers from a certain country. I have a hypothesis that somehow, countries visually influence photographers born inside their borders. The Austro-Hungarian Empire gave us so many photographic giants that discussing only 5 was a real challenge – I had to omit a few photographers who were of utmost importance in the history of the twentieth-century photography.

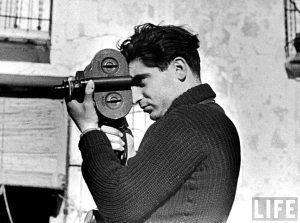

I remember the first time I noticed that Hungary’s particular geography had given birth to some great photographers. I was watching a more or less biographical film about Ernest Hemingway & Martha Gellhorn. In one scene, Gellhorn (played by Nicole Kidman) asked Robert Capa (Santiago Cabrera) how she could take good photographs, like he did. He replied that she just “needed to be Hungarian”. I can’t find the exact scene where this dialogue happens, but it takes place in the context of this other scene, where the character of Capa is seen doing what he did best.

Below is a list of 7 – not 5! – Hungarian photographers whom I am convinced have contributed a great deal to photography. I have retained their birth names, since a lot of them changed their names for various commercial or political reasons. An interesting thing here is that most of these photographers were contemporaries.

Martin Munkácsi was a prolific photographer, very famous indeed. He shot a lot of things, from sports, to politics and, of course, the amazing life of the streets. The great innovation his work brought to the table was that his sports images were meticulously composed action photographs. They required a high level of aesthetics, technical skill and strength, because many of them were made not with a 35mm camera nor a medium-format, but 4×5 large-format camera.

I want to highlight two images. One is the first image I saw by Munkácsi, taken with a large-format camera, handheld. No wonder this guy was considered to be a tough photographer. The other one is this picture taken in Liberia of three boys running towards the sea. This particular image was the trigger that ignited Cartier-Bresson's enthusiasm for photography – and the only image acknowledged by Cartier-Bresson to have influenced him at all.

You can see more of Munkácsi’s work here.

Usher Fellig, a.k.a. “Weegee”, was born during the Austro-Hungarian Empire (but if we get picky, he was born in Zolochiv, now part of Ukraine). Weegee was best known for his crime-scene photographs. The most curious thing about his work is that he always seemed to be the first to arrive at a crime scene, even before the police. It was known that he sat around the police station listening to the station transmitter. He gained his name of “Weegee” because people thought he used a Ouija board for being able to get quickly to the events.

His most notable photographs were taken with a very basic yet reliable camera, a 4×5 Speed Graphic. He had it set at f/16 at 1/200 of a second, with flashbulbs and a set focus distance of ten feet. He also developed his images in the back of his car so he could sell his work to the press faster than anybody else.

You can see more of his work here.

Born as Kertész Andor, André Kertész was a Hungarian-born photographer largely known for his groundbreaking contributions to photography, especially in the fields of composition and the photo essay as we know it today. If I was in the strange position in which I could pick only one photographer's work to take with me (preferably in book format) onto a desert island, I would pick Kertész. He dived into a lot of niches and styles, and performed with great aesthetics in all of them. If you want a quick study of photography at its best, Kertész's work is the way to go.

From the complex to the beautifully simple, his work is a blast.

Escher was born in Szekszárd, in Hungary’s Tolna region. He worked as a cinematographer on newsreels during the short-lived Hungarian Soviet Republic. Later he worked for the newspaper Pesti Napló in the ’30s and ’40s. He died at age 75 in Budapest in 1966. He had a thing for rhythms and patterns, but with people as subjects, which makes his type of photography both innovative and timeless.

You can see more of his work here.

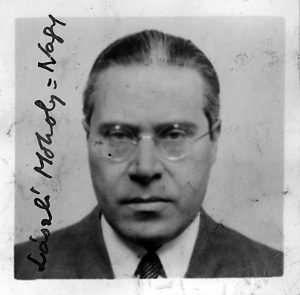

László Weisz transformed himself into László Moholy-Nagy, and he was known for being an important professor in the Bauhaus school. He was highly influenced by constructivism and a strong advocate of the integration of technology and industry into the arts. He also got involved with other art movements besides Bauhaus: Constructivism, Dada, Expressionism, Modern art, and Good Design. He experimented with photosensitive materials and called his process “photograms”.

My favorite photograph from László is this one.

That was the original name of the great Brassaï. He was a variously disciplined artist, in addition to a photographer. Brassaï was one of the numerous Hungarian artists who flourished in Paris beginning between the world wars. After arriving in Paris in 1924, Brassaï quickly became a fierce and obsessive observer of Paris’s rich nocturnal life. If you like night photography, this photographer needs to be your master and guide. There is a fantastic book I had the chance of holding once: it’s called, simply, “Brassai: Paris by Night”.

You can see more of his work here.

And last but not least, the almighty Capa.

There’s nothing new to say about this

legend, other than that his original name was Endre Friedman, not Robert Capa. Here is one of the many sources of information you can access about Capa.

We hope you have enjoyed this article. Please tell us if you have an opinion on my theory about how a nation’s intrinsic nature influences its photographic population.