I, like many others, have waxed lyrical about the halcyon days of film. Like many of a certain age, we remember fondly the reassuring clunk of a shutter button or the feel as a film is propelled one frame closer to the end of the roll.

Film, in recent years, has made a revival, and why not? Its fun, it has a unique look and it can teach you many things about photography. However, those of us that do write about film tend to do so through a pair of slightly grubby rose-tinted filters.

There are many reasons why film was not so great. So come and join me on a nostalgic, yet more realistic and hopefully humorous trip to the days of film.

Film Advance

As I mentioned, there was a peculiar sense of satisfaction as one frame of film advanced to the next. Unless of course, it didn’t. Loading a film should have been an easy task, but if you were under pressure, or your hands were cold, it could often be harder than knitting a tripod.

In the modern era, if a card fails or needs formatting we have a lovely little red flashing message on our LCDs. Back then though, the first time you realized the film had not advanced was when you received back a roll of extremely unexposed film. It was crushingly disappointing and makes it even more remarkable that so many of us persevered.

It looks so simple yet could easily go wrong. By Alan Levine

Batteries

We love to moan about the batteries in our digital cameras. Before you do, spare a thought for the photographers of last twenty years of the film era. You see this was the time of automation in cameras. Auto exposure, autofocus, and motorized film advanced. Of course, these wonderful technologies were not powered by pixie dust and magic, they needed batteries. Batteries of thirty years ago look much like batteries today. However, looks could be deceiving, for they had little of the power and few were rechargeable.

Most SLRs used a small lithium battery to power exposure meters and electronic shutters. To be fair these could last years but that was the inherent problem. We did not expect them to fail and so were quite often very surprised that they did.

Our surprise was often supplemented with annoyance because the battery had failed at the top of a beautiful mountain at dawn and the nearest retailer, usually a jewelry shop, was at least 10 miles away and not open for another four hours.

Professional motor drives were another thing altogether when it came to batteries. They often used four to eight AA batteries that would take the best part of a football match to change.

Motordrives were veritable battery vampires. By Gábor Dobrocsi

One-Hour Minilabs

By the late eighties, every village had a one-hour minilab. There were a couple of problems with this though. Firstly the concept of one hour was directly related to your financial well being. To get your films back in one hour you often had to pay two or three times the normal price. Even then the concept of time was quite fluid.

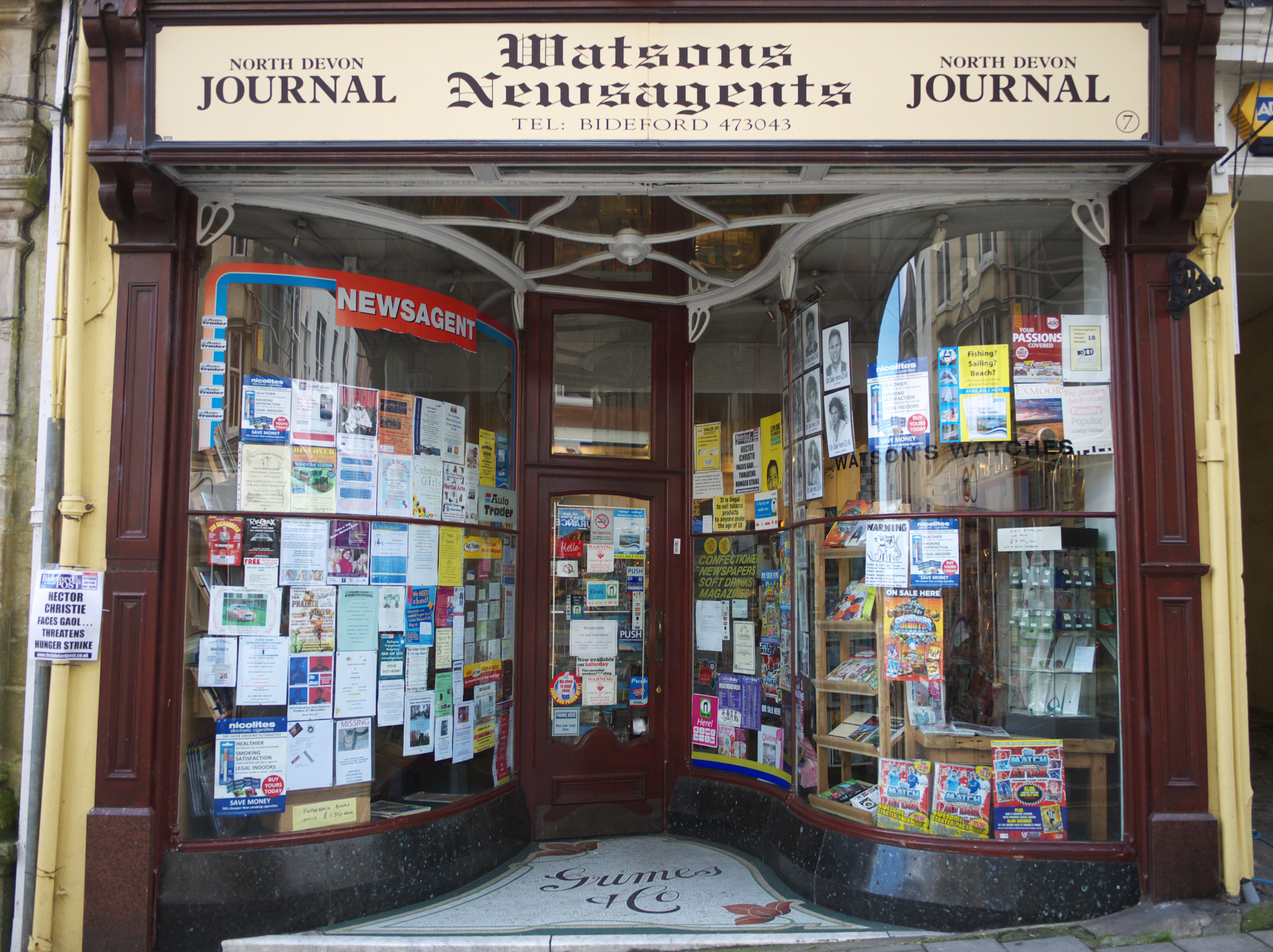

Secondly, while you might expect one-hour minilabs were the preserve of photo shops and other photographic professionals, they weren’t. Drug stores, railway stations and even newsagents all got in to the one hour craze.

It seems odd now that you could go down to your local store order a pint of milk, twenty Benson and Hedges and have your film developed. Often the colours of the return prints looked not unlike the colour of the B and H nicotine stains on your ceiling.

Cigarettes and Film Processing at your local newsagent. By Joe Lanman

Cost

Moving on from one-hour minilabs we come to cost. It was a time when every shot cost money. Not just the rolls of film, a few dollars per 36 exposure roll, but the costs of processing, printing and storing them. Already discontent with the quality of processing from your newsagent, you would now have to go and buy some archival sleeving for your precious negatives, replacing the secondhand newspaper pouch that your film was carelessly thrown in to. You would need photo albums to store prints and slide projectors to bore your friends, assuming you could afford friends. Photography has always been a money pit, but in the days of film, the pit was bottomless.

Dust

We older photographers laugh in the face of dust bunnies. You see we had dust dinosaurs, great big pieces of carpet fluff or cat fur that would magnetically find its way onto drying film even in a hermetically sealed chamber. You might be balder than Kojak and yet a long curly hair would still find its way onto your film. By the time it came to print, your negatives would look like a slightly matted Persian rug.

To remove all this muck we would use cans of compressed air. We were told to hold them upright but even as we did, they would expel 50% air and 50% ice cold propellant, freezing our negatives into something resembling a well preserved wooly mammoth. Every print ended up look like a black and white close up of a badly folded map.

More dust than an old rug. Film was a dirt magnet when wet. By Dmitriy Fokeev

Film is fun, it's educational, it gives amazing results, but it is by no means perfect. There is no reason why film cannot sit beside digital in our repertoire of skills, but maybe its time to let go of the idea that the days of film were some kind of celluloid nirvana.

When the late British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan said “You have never had it so good” he might well have been predicting the era of digital photography.

Let us know your less than nostalgic memories of film.

3 Comments

Until comparatively late in the analogue period of my photography, I shot mostly black & white. Because I could develop my own films, and make my own prints. I commandeered the cellar beneath the kitchen of the house, and converted it into my darkroom – spending many happy hours in the red glow of the safety light, printing and “dodging” my enlargements, the smell from the chemicals in the nearby chemical baths filling my nostrils. And then taking over the bathtub upstairs, next to the kitchen, to finish the process by washing the prints to relieve them of chemicals which would otherwise make them fade.

With black & white, you can leave the red safety on during the process, you can watch while the print starts its time in the bath of developer, as the image starts to appear on the paper and gradually turns into your photo. There is a special magic to this, which everyone who has made their own prints experiences.

You mention dust – with the best will in the world, there is also a problem with tiny air bubbles, leaving small white holes in the prints. And after the bathtub, and drying the prints, there is a process of “spotting” which gives you manual skills you’d never dreamed of before, until you are finally satisfied with the print. Even better – retouching colour enlargements, with a limited palette of suitable colours. And all the retouching done with a brush so fine it barely has any hairs on it – nothing thicker is safe on the print, and unlike Photoshop or the other digital post processing problems, each touch of the brush puts an irreversible change on the print. One careless mistake, and it’s back to the cellar for another copy of the photo!

You’re right, of course – the physical and financial process of film photography was such that digital – to me at least – came as the most wonderful liberation to shoot as often and as many frames as I wanted – and as such it definitely improved my photography. While I would never want to go back – to lose that freedom and flexibility – there is, for me, something missing sometimes, especially in terms of my personal photography. There was something indefinably satisfying in the mixture of art and physical craft that was required to make images on film and paper.

For that reason I’ve recently re-invested in some film cameras, a scanner and some chemicals (cameras plural! So great that we can now buy analogue cameras that were only in our dreams pre-digital). I have to say that the hybrid analogue/digital workflow is very satisfying (especially developing my B&W rolls) and, what’s more, eliminates many of the downsides described in this excellent piece. Not only that, it even slightly ameliorates my GAS as every different film type is like getting a new sensor.

I’ll close just by saying that digital is great and I love my Fujifilm X-T2, but anyone who says it is now at a stage where it makes film obsolete has either forgotten, or never seen, the beauty of a well-made silver-based image.

Something I learned a long-ass time ago:

Always check that the rewind knob, turns as you advance to the next frame.