With the digital age truly here and here to stay, today we are going to take a brief but nostalgic look down memory lane at the history of film, from the earliest days to the current state of the art.

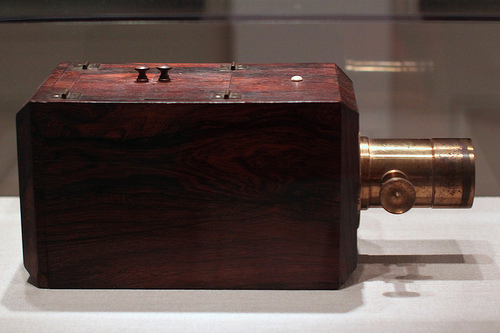

The Rise of Daguerreotype

In common with modern digital sensors, film is just a way of recording the light to a physical medium. The very earliest film was called a Daguerreotype and was actually a copper plate coated with light sensitive, silver iodide. Those of you use to the crazy ISO speeds of modern DLSR’s may have struggled with the sensitivity of Daguerreotypes, the very earliest of which, in good light, had exposure times of up to eight hours. Eventually, the process was streamlined down to get exposure times in the minutes rather than hours, but even for this, portraits still required the subject to sit motionless, usually with a head brace, for the entire exposure. This is often why early Victorian photographic portraits look so stiff and uncomfortable.

Kodak Joins the Fray

The next major development in the evolution of film came in the 1850’s with the use of thin glass plates rather than copper giving a much better image quality. In 1885 the Eastman Kodak company introduced the first flexible film – basically a photographic emulsion coated onto thick paper, rapidly followed in 1889 by the first “plastic” film, made from highly inflammable nitrocellulose.

In 1908, Kodak introduced the first cellulose based film also called “safety film” – a phrase that was imprinted into the sides of most Kodak films until recent times. This was perhaps the first film that came in a form that we would recognize today.

What About Color?

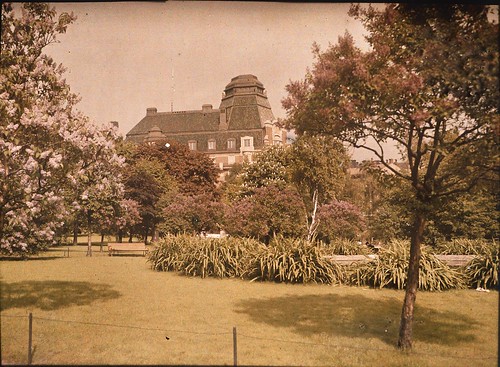

Color came to film surprisingly early on, in 1861, when images were produce using a three plate system. Not surprisingly, this was a highly cumbersome and time consuming process and was only available to the wealthiest practitioners of what then was a highly expensive profession. Color came of age in the early 20th century but it was not until 1936 that color photography matured for the masses.

It was again Eastman Kodak that made that step, this time with arguably the most iconic film in photographic history, Kodachrome. Many, who learnt photography in the digital age, may have read about the demise of Kodachrome and the final closure of Kodachrome processing, but not truly understood the impact this film had on film photography. Kodachrome was revered by professional photographers for its vibrant colors and incredible sharpness and many a National Geographic photographer would use thousands of rolls of it on assignment.

The biggest issue with Kodachrome was the processing, which was a highly complex affair and only available from Kodak designated laboratories. To counter this, Kodak also introduced its E series of processing, cumulating with E6 – a much simpler process that could be carried out in a home lab. It was the E6 and its color negative counterpart C41 that sparked a technology race, primarily between Kodak and Fuji to woo-over professional photographers with faster, higher resolution and better contrast films in the 1980s.

By the mid 90s film had reached it’s technical peak. Every high street would have several photographic mini labs all vying to be the fastest, so would have your prints ready within 30 minutes, photographic film was plentiful and cheap, with a large selection of manufacturers, types and speeds.

The Impact of The Digital Age

The fortunes of Kodak and Fuji have very much been the story of the digital age. Whilst Fuji recognized early on that digital would make a huge impact on the photographic industry, Kodak were much slower off the mark, believing that professional photography would remain film based. Although the slow death of film took place perhaps over the first decade of the millennium, its most dramatic decline was probably from 2004-2006 when consumer level digital cameras became as cheap as film cameras.

When National Geographic photographer Steve McCurry clicked the shutter on the last roll of Kodachrome, he effectively consigned 35mm film the archive of technology, to sit alongside Laser-disks, audio cassettes, betamax and the fax machine. For many a photographer brought up with the feel of celluloid in their hands, it was a sad sad day.

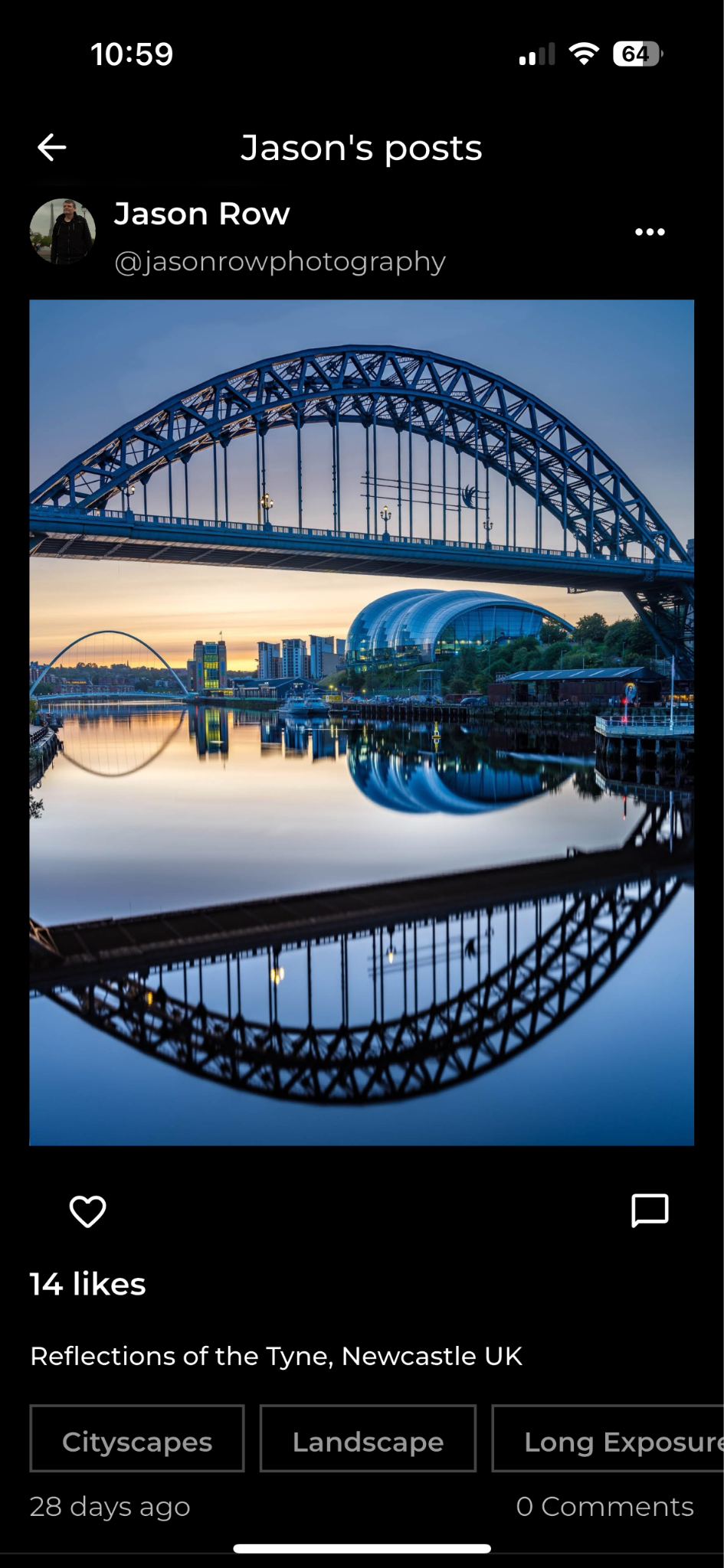

Jason Row is a British born travel photographer now living in Ukraine. You can follow him on Facebook or visit his site, The Odessa Files. He also maintains a blog chronicling his exploits as an Expat in the former Soviet Union

1 Comment

I purchased a 35mm fuji discovery

1000 zoom what is it worth?[I paid $1.70] at goodwill,I missed out on a

polaroid 600&olympia 35mm.