Beth Moon is an artist and photographer from San Francisco Bay Area, who has gained international recognition for her platinum prints. She studied fine art at the University of Wisconsin and her work has appeared in numerous solo and group exhibitions around the world and is also held in numerous public and private collections in museums.

Beth was unhappy with the tonality and stability of ink-jet printing and started experimenting with alternative printing processes. She found platinum/palladium printing to be an ideal process for her creative vision and focused on mastering this technique that she uses to do all her printing by herself. These prints can last for centuries and portray a common theme of time and survival for both her subject and the photographic process.

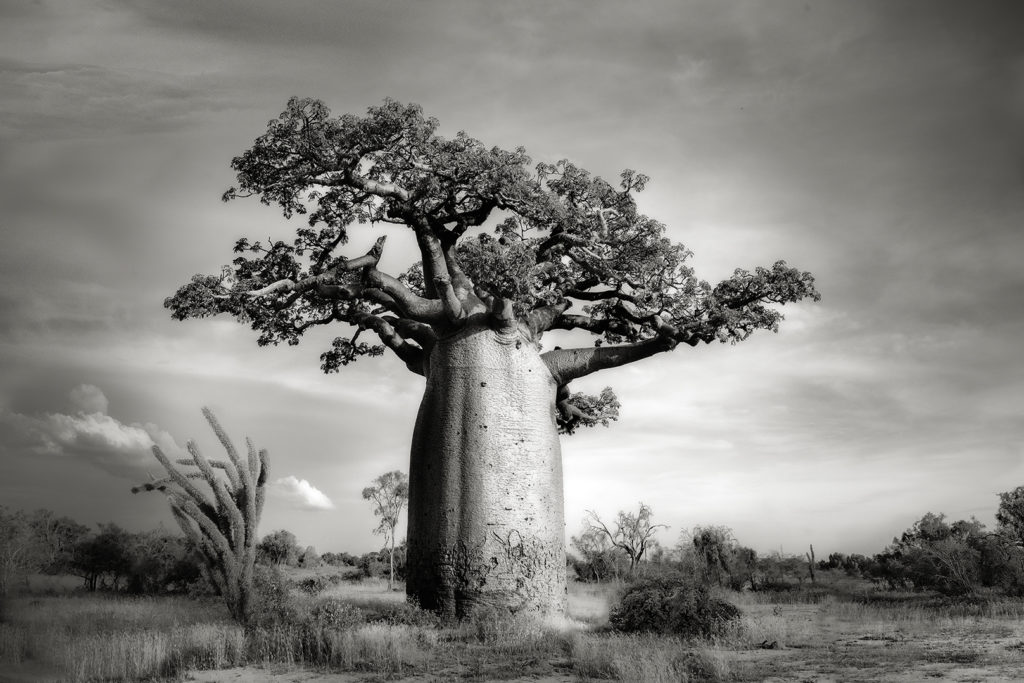

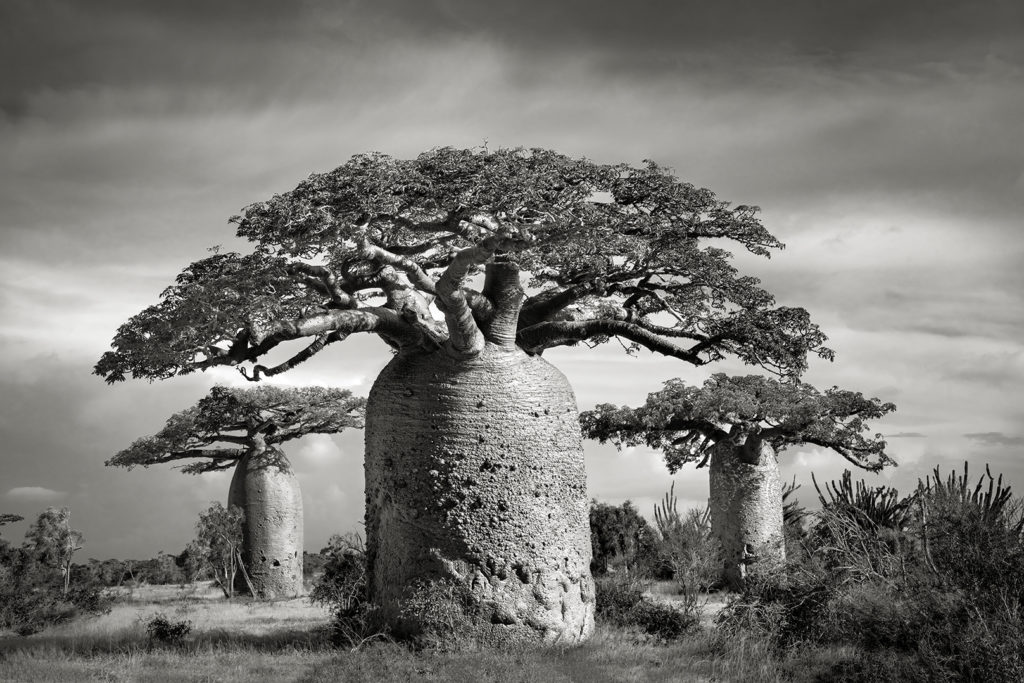

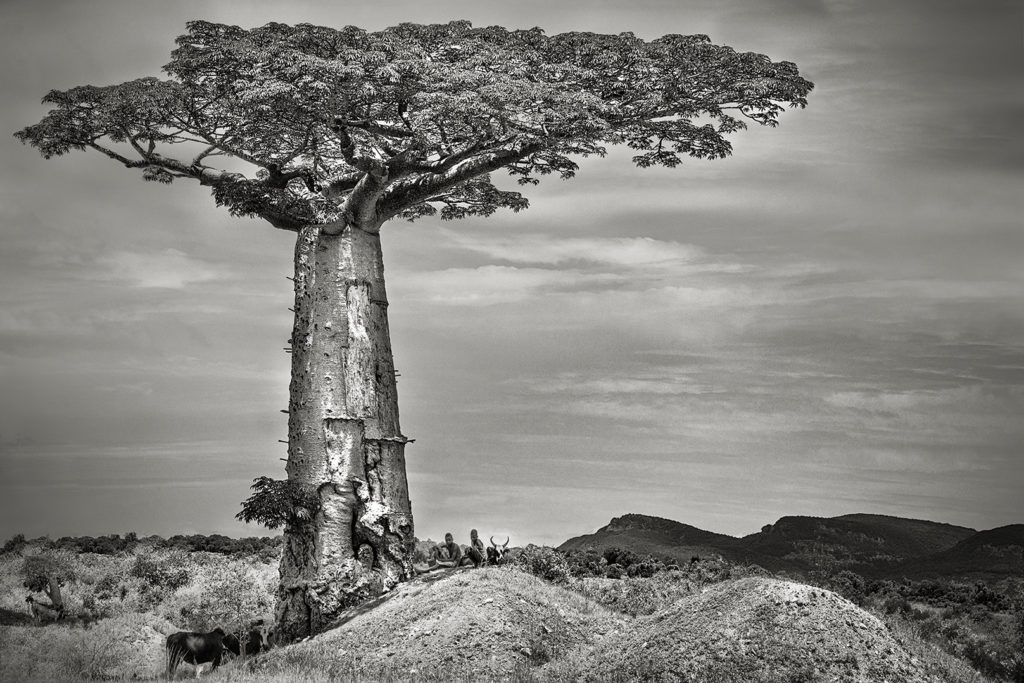

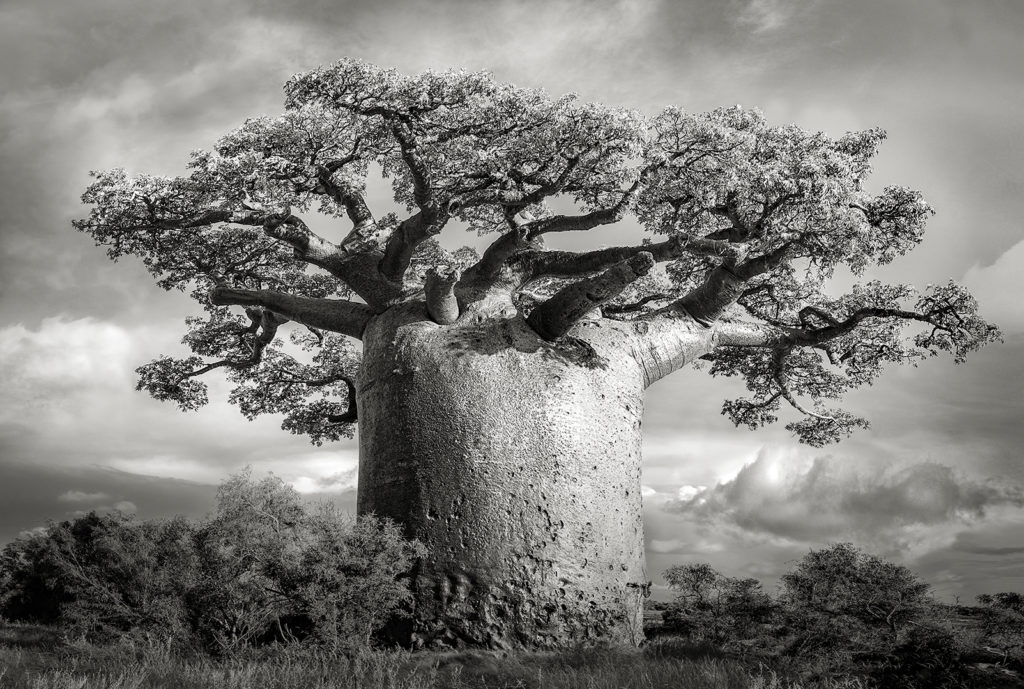

Beth has been documenting the ancient and Madagascar's most sacred baobabs since 2006. She has captured the rich textures and characteristics of these trees in dramatic black and white. Her photos show how the years of long drought cause devastating effects on these trees leading to rapid reduction of the baobab population.

Here, Beth shares with us some of her experiences with the baobab trees along with some photographs.

In January 2016, a thunderous boom was heard. One of Africa’s oldest trees, the Chapman’s baobab, had collapsed. Memories of my visit to the tree two years earlier flooded my mind. This is hard to believe, the tree had looked so strong and healthy.

Then, in June 2018, shocking headlines began to appear in global media.

Last March of the “Wooden Elephants”: Africa’s Ancient Baobabs Are Dying

The New York Times

Baobabs Are Africa’s Oldest and Most Beautiful Trees, But They’re Under Threat

The Independent

Shocking and Dramatic Death of Giant African Baobab Trees Possibly Linked to Climate Change

The Daily News

The guide who led me to various locations throughout Botswana writes to tell me the trees that we camped under at Kubu Island have collapsed. “From the cluster of trees on the NE side, at least two have fallen,” he reports.

Scientist Adrian Patrut and his team have been measuring, radiocarbon dating, and documenting the largest and oldest trees in the Southern Hemisphere for the past decade. Professor Patrut and I have been sharing information on trees for several years.

He set out to carbon date the oldest trees, hoping to find information about the climate over the past millennia. After cataloging so many collapsed baobabs, they came to a startling realization: nine of the thirteen oldest and five of the six largest baobabs that they sampled had died in the past twelve years. The trees were in danger.

On November 3, 2018, Professor Patrut wrote to tell me that he has received news from Madagascar. He writes, “The Tsitakakoike baobab, the biggest sacred baobab, split and toppled several days ago.”

Scientists agree that man-made climate change is the most probable cause. It is evident that higher temperatures and drought are responsible, but further research is necessary.

The trees in danger are in the southern parts of the African continent, in Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Madagascar, where the temperatures are warming faster than the global average, and drought is intensifying with each year.

By contrast, baobabs are doing well in many parts of northern Africa. This raises the question, are the trees dying because of rising temperatures or because they are old?

“Such a disastrous decline is very unexpected,” Patrut said. “It’s a strange feeling, because these are trees which may live for 2,000 years or more, and we see that they’re dying one after another during our lifetime. It’s statistically very unlikely.”

So why do we need old trees? A study conducted by scientists at the University of Hamburg suggests the older a tree is, the better it absorbs carbon from the atmosphere. Older trees are taller, can reach the top of the forest canopy, and have consistent access to the sun.

Younger trees are more sensitive to changing conditions of rainfall and sunlight than older trees. Almost 70 percent of all the carbon stored in trees is accumulated in the latter half of their lives. This points to a real benefit of old trees in our battle against climate change.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal and carbon-storing capacity, old trees are biologically critical. They contain superior genes that have enabled them to survive through the ages, resistant to disease and other uncertainties. Their genetic heritage is invaluable for reforestation.

Each tree embodies a unique habitat created only by the passage of time. These trees serve as reservoirs for rich communities of plants, animals, insects, lichens, and other life forms. They provide a habitat for wildlife. They are the backbones of ecosystem integrity and biodiversity.

No longer able to ignore the devastating information before me, I decided to travel back to Madagascar to document the dying tree. We only need to look to the past for such examples as the Wooly Mammoth and the Sabre-Toothed Tiger. After they are gone, that’s all there is.

My journey to the tree was filled with adventure. Alternative paths into the forest led to the discovery of trees I hadn’t seen before. In the presence of old trees, I am reminded there is still grace and beauty in the world. Such thoughts lead me past grief into hopefulness. By honoring the trees that remain, we celebrate the joy and splendor of our natural world.

If you like Beth's work and wish to follow or see more of her works, here are the links to her website and social media accounts.

- Beth's Website

- Beth's Facebook Page

- Beth on Instagram