You have probably noticed we are talking more and more about video here on Light Stalking. The reason for that is simple. For the average photographer, the convergence between still and motion imaging is now pretty much complete.

With the flip of a dial or press of a button, we can change from shooting a 25mp still to shooting 4K video and get stunning results from each. However, there are some considerations when shooting video when compared to shooting stills.

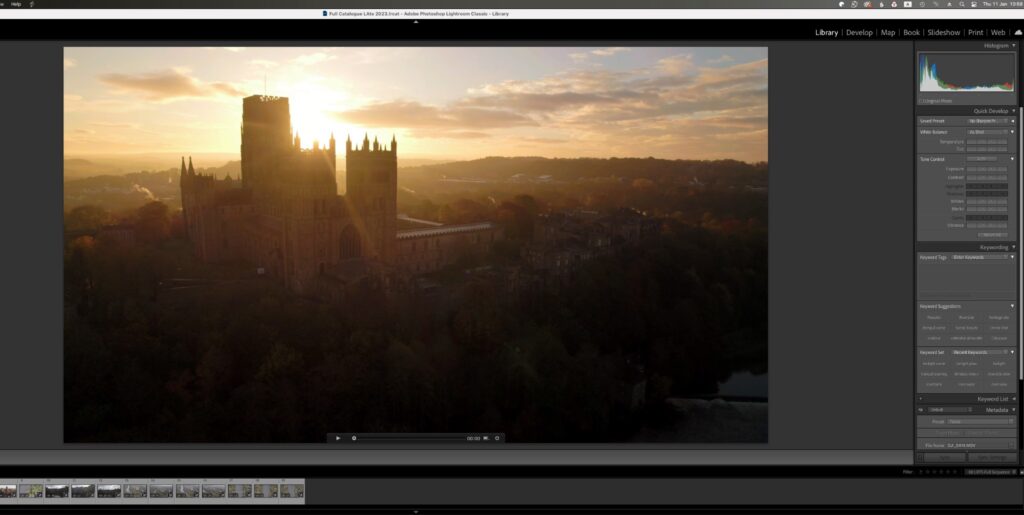

One of the most important is shutter speed. It perhaps has an even greater impact on the visual look of video than it does with stills. The simple fact is, that for most video footage we need a fairly slow shutter speed, and that means using ND or Neutral Density filters. Today we are going to explain why.

How Video Works – 180 Degree Rule.

Much of the way we shoot video these days is still based on the way cinematographers have shot films over the last century. Films are generally shot at 24 fps, frames per second. This is fast enough that the eye cannot see any perceptible change between each frame.

However, this is only half the story. As in still photography, the faster the shutter speed, the more the motion is frozen. In film or video, we need to maintain a certain amount of motion blur in order to blend each individual frame into the next. In order to achieve this we use the 180 degree rule.

Put simply, the 180 degree rule states that your shutter speed should be twice that of your frame rate. If you are shooting your video at 24fps then your shutter speed should be 1/48th or a second. If you are at 30fps then your shutter should be 1/60th. Not all camera’s will be able to exactly double each frame rate but you should aim for the nearest option. In the case of 24 fps you will probably find 1/50th is the closest shutter speed.

If you go for a higher shutter speed, you will find that your video footage becomes less fluid looking. A classic example of deliberately using a high shutter speed is in the opening sequences of Saving Private Ryan. Here, the staccato looking footage is meant to make you feel uneasy and as if you are in the battle.

I am sure you have noticed by now the main problem with the 180 degree rule. The relatively slow shutter speeds needed for smooth footage can be problematic in bright light or when trying to obtain a shallow depth of field. This is where we need the neutral density filters.

What Are ND Filters?

As photographers, many of us may already own neutral density filters. We use them in stills to get the ultra slow shutter speeds needed for ethereal looking water or clouds in landscapes. They might also be used when shooting flash outdoors to get our shutter speed low enough for the flash to synchronise.

Put simply they are darkened glass or acrylic filters, placed over our lenses to reduce the amount of light reaching the sensor. They are graded by stop numbers, cutting out 1, 2 or 3 stops of light. There are also much more dense filters that cut 6, 10 or even more stops of light.

There are two ways of rating the density of filters, optical density, and ND Factor. Optical density starts at 0.3 for a 1 stop reduction in light 0.6 for two stops and so on. ND factor starts at ND2 for one stop reduction, ND4 for 2 stops etc.

As videographers, we need to have a selection of ND filters in order to obtain the precise shutter speed we need. Although we can, of course, use aperture to get the shutter speed down, we don’t want to go beyond the diffraction limits of our sensors. In the brightest light, often even the lens' smallest aperture may not lower the shutter speed sufficiently.

This can become even more problematic if we shoot LOG footage. To obtain the low contrast curves in LOG, cameras often boost the ISO. For example, my Fuji X-T2 has a base ISO of 200 but if shooting LOG, that ISO becomes 800, adding 3 extra stops to my exposure. With this in mind, what ND filters should you get?

Best ND Filters For Video

There are two basic systems of filters, the screw in types and the square filter systems such as Lee. If you are using multiple different lenses with different filter threads, then you have two options.

The first is to invest in a set of ND filters to fit your largest lens and buy stop down rings to fit to your smaller lenses. The second is to invest in a square filter system.

A square system although more expensive makes it easier to adapt to all lenses and is also easier when stacking neutral density filters.

There is one last option, variable neutral density filters. These allow you to turn an outer ring like on a polariser. As you do so, the filter gets incrementally darker or lighter. Variable NDs can reduce the light to your sensor anywhere from 2 stops to 8 stops. However, they are not without problems.

Variable NDs can exhibit bigger color shifts and more banding, especially on wider angled lenses. They are also significantly more expensive, especially if you aim for a good quality model. They can, however, be used with most square filter systems with the use of an adapter ring. This gives you more options if you want to shoot with other filters such as graduated NDs

If you are serious about the quality of your footage then a set of ND filters are a must. Most dedicated video camcorders have them built in, however, very few stills cameras incorporate them.

Given the incredible video quality that some still cameras are capable of now, it's not a great leap of the imagination to suggest that future models may well include ND filters. However for now, as a videographer using a DSLR or Mirrorless system, an ND system is something you are going to need to get silky smooth cinematic video.