I am sure like me, many of you have spent a little time in art galleries. Also like me you may well have admired the many beautiful, old portraits that these galleries often display. You may well have wondered about the back story of these portraits. However, if you did delve a little deeper into the history of these paintings, one thing would become apparent. The subjects, for the most part, were all wealthy, important people. People with enough money to commission an artist to paint them.

Recently I had a bereavement in my close family. In sorting through my relative’s possessions, we found a treasure trove of wonderful photos. They were not photos that you or I might take, they were simple family memories. That got me thing as to how privileged we are these days to have such photographic memories, it has not always been the case.

Memories Before Photography

If you were an average working-class person in the pre-photographic era, the chances are the only memories you might have of a loved one would be some ornaments, perhaps some clothes, or other personal items. It’s pretty unlikely that you would have any visual reference such as a painting or even a drawing. These artworks were well beyond the reach of the average person.

The advent of photography changed all that, but not overnight. It took pretty much the entire Victorian era for portrait photography to go from a pursuit of the very wealthy to something the working class could partake in.

Victorian Portraiture

As photography advance in the mid 19th century, it became more accessible to the upper middle classes. A new breed of professional photographers was to emerge, the portrait photographer. Whilst the equipment and processes were time-consuming and expensive, the end results could be produced fairly cheaply. This meant that it became possible for the middle class and indeed some working-class people to pay to have their portrait taken.

However, for many people a portrait was still a luxury that they could ill afford, so most people on limited wages would not have one taken. That is until a close relative died.

From the mid-1800s a new type of portraiture took hold, the memento mori or death portrait. Victorian times were brutal on many families. The Industrial Revolution and mass migration to cities had created the perfect storm in which infectious diseases could thrive. Many families were decimated, not just the elderly but often children.

The memento mori was a way of visually preserving a lost love one for eternity. As gruesome as it sounds, very often the living, would pose with their dead relatives in a single shot. The dead person standing propped up next to the living. In order to make the dead looking more like the living, often the portraits were touched up. One of the more common retouching techniques was to paint in the eyes.

Improving healthcare and a certain Mr. Eastman spelled the end of the memento mori by the late 1800s. The democratisation of photography was about to get a massive boost.

The Kodak Moment

George Eastman brought the world the Kodak camera. It was literally a box with a 100 exposure roll of film that you sent back to be developed. Its significance though is that it enabled photography for everyone. It was a cheap, point-and-shoot camera that people with no photographic experience could use and effectively gave birth to the family snapshot.

In 1900 Kodak released the Box Brownie, an even simpler and cheaper camera that was extensively marketed towards children.

The effect of Kodak on the democratisation of memories cannot be underestimated. Now people could take photos of their own, living relatives easily and cheaply. These photos would be stored in albums for friends and family to look at and of course for future generations to marvel over. The family snapshot had arrived.

The Film Era

Through the film era, photography became cheaper and easier to do. Drug stores would offer processing services whereby you could get your rolls of film processed and printed for a few dollars. It would still take several days to a week to see the end result though.

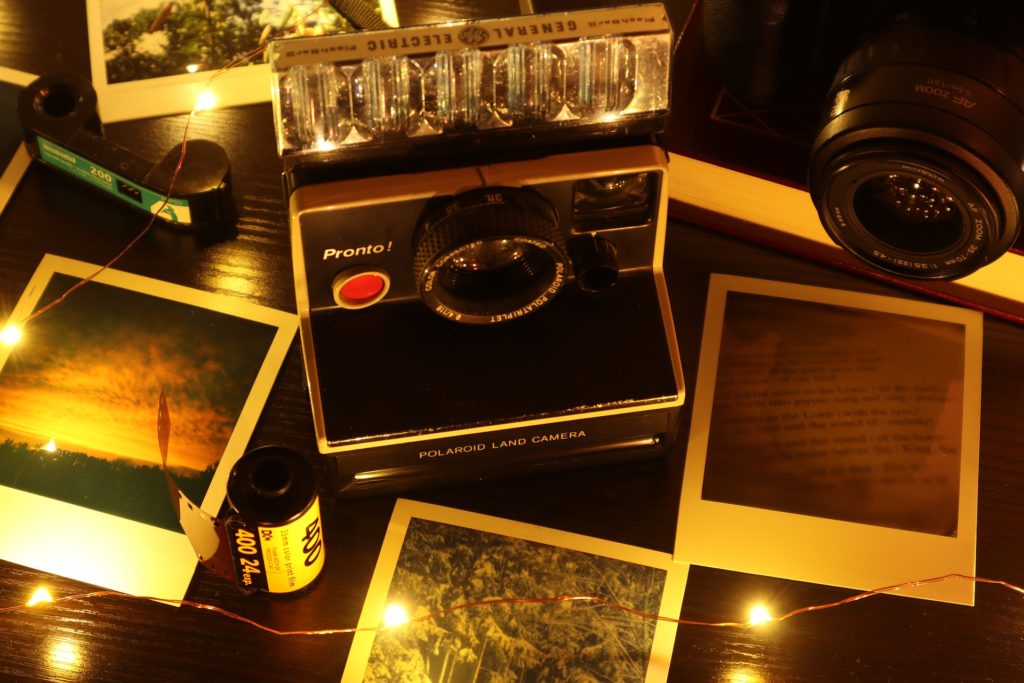

Two other milestones in the democratisation of memories were the advent of the Polaroid and the introduction of the one-hour minilab.

Polaroid became massive in the 1960s. Families could literally shoot their memories and see them a minute or so later. Friends would often swap pictures with each other getting different perspectives of the same event. If there was one flaw to using polaroids to preserve memories it was the longevity of the final print. Unless well protected, a Polaroid could start to fade within a decade. Storing them for prosperity meant keeping them in the dark and away from moisture.

The one-hour minilab gave people the ability to get their memories back in 60 minutes. In later years this was down to 30 minutes in some cases. There was however a premium to pay, not only in cost but often quality was compromised.

The Digital Conundrum

Of course, the ultimate conclusion to the democratisation of memories has to be the digital era. We can now take 1000s of amazing photos on tiny cameras and share them globally. That, however, has lead to a devaluing of the power of photography for creating lasting memories.

The shoot it and delete culture that we live in now can lead to some incredible memories simply being deleted. This might be because they are not perceived as the perfect shot. It might be because we were simply making space on our memory cards.

Another issue is how we preserve digital images for the future. In the film days most rolls of film got printed. My relative’s photos were all stored in boxes that hadn’t seen the light of day for decades. Once found it was a treasure trove of memories.

Digital is perhaps more difficult to preserve because it is not tangible. The obsolescence of formats, to me, is a moot point. Formats will always be able to be converted. However, let’s assume one of your relatives stores their images on a hard drive and puts them in a box for safekeeping. In the future, when that box is opened, will there still be the technology to read that drive? The answer is probably yes, but the real question is whether the person finding that drive will be bothered to track down and buy a device to read it. That, to me seems unlikely in the majority of cases. In turn, it makes me a little sad about how our own future generations will rediscover the memories that we are making today.

1 Comment

Ultimately, this last issue regarding preservation of memories likely means that any digital photographs you want to leave to posterity will need to be made into a print. It is an interesting twist of technology.