Whether you are a seasoned pro or relative newcomer, most photographers have heard of HDR, or high dynamic range photography. Those of us who have been around a while might have painful flashbacks when the letters HDR are mentioned.

There is a good reason for this. HDR became a massive trend/fad in the mid-2000s and whenever there is a fad in photography, it can lead to “misuse” of the technique. More on that later, but to get started we really should look at what HDR actually is.

What is HDR?

The clue is in the name, high dynamic range allows us to create images beyond the sensor’s capabilities. Modern sensors are pretty amazing, the best can capture up to 14 stops of dynamic range. However, in very high-contrast scenes, there may well be more than 14 stops between the lightest and darkest parts of the image.

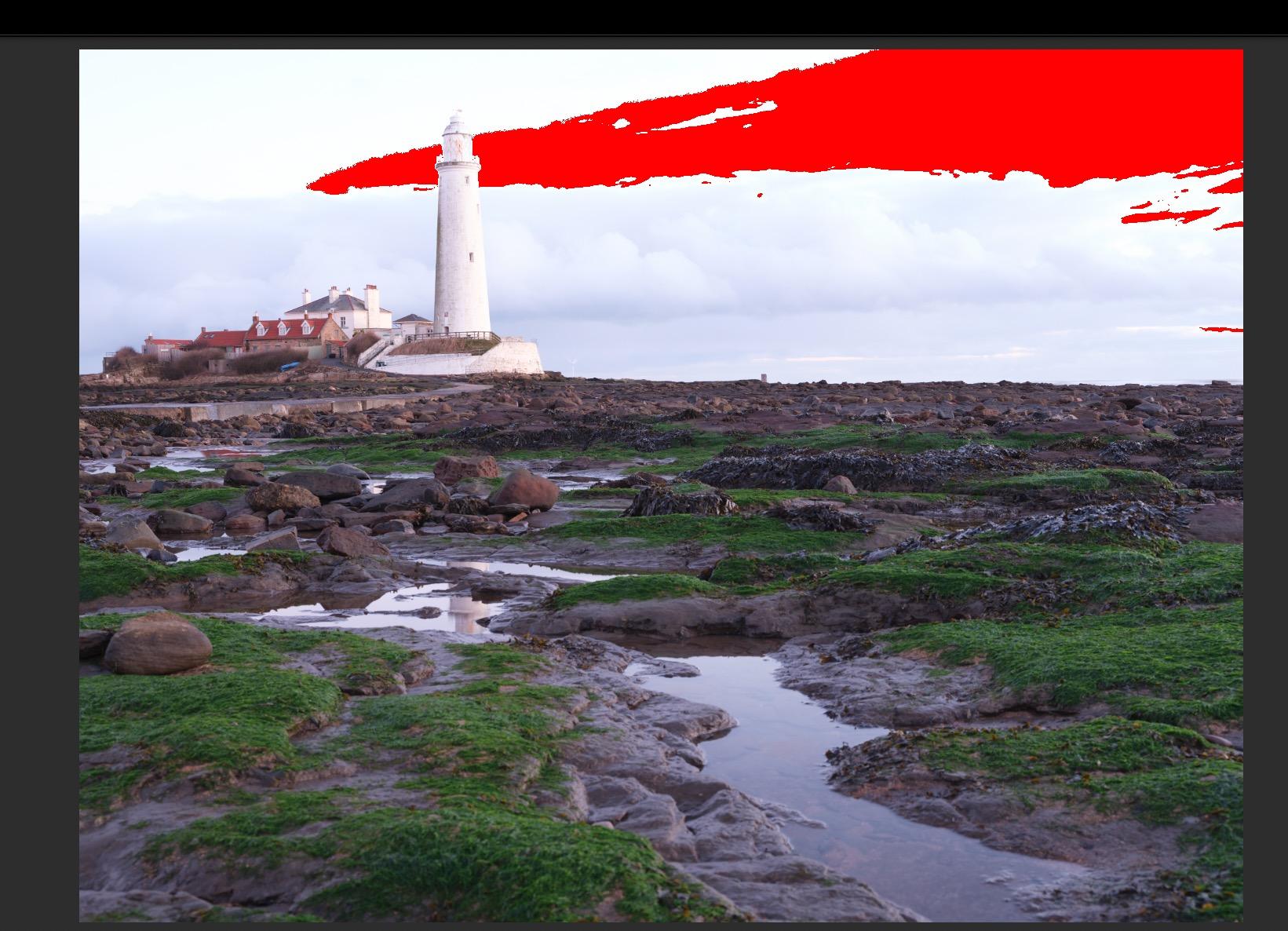

One way we can deal with that is to expose either for the shadows or the highlights. For example, if our sky is washing out, we can reduce exposure to bring it back. However, this will make our shadow areas become even darker, often to the point that we cannot see any detail in them.

Both shadows and highlights cannot be recovered if they are beyond the range of the sensor. Lighting crushed shadows in post-production will result in a noisy flat mess. Reducing clipped highlights will give you a uniform grey area with no definition.

With HDR however, we can maintain detail in both shadows and highlights. We do this simply by merging a series of images in post-production. Some of the images will be underexposed, some over, and one will be on or around the metered exposure. When we combine those images we get a shot that goes well beyond the dynamic range of our camera’s sensor.

HDR’s Garish History

Great, I hear you say, but why does HDR have such a bad rap amongst older photographers?

Well to understand that we need to go back a little bit in time. HDR got its bad reputation in the early days of digital photography. However, the technique itself predates the digital age.

A form of HDR was around for decades in film photography. The principles were the same, shot under/over and normal, they were just combined in an enlarger rather than an app.

Digital photography arrived to the masses in the early 2000s. Early cameras produced decent images but their sensors had much less dynamic range than their modern counterparts. For that reason, digital photographers adopted the film technique of combining images.

These days we are used to a virtually one-click solution to combine HDR shots, but back then, it required dedicated HDR software to do the job. There were quite a few apps out there, all competing to get their share of the market. They did this by offering as many features as possible. One of the most important tools in HDR is tone mapping. It was the over-enthusiastic use of this that led to a plethora of very garish, bright colorful images.

Back then, social media was in its infancy, yet like today, the more striking an image, the more likes it would get. It leads to a virtual arms race of overblown HDR images being posted to sites such as Flickr and Myspace. If your image did not get enough attention, you would reprocess it to look even more garish.

This was not only a trend amongst new photographers but also togs coming from film. It was the first flush of a new trend and everyone wanted a part of it.

By the late 2000s, people began to realize that garish HDR images were often not actually good shots, just striking shots. The fad started to die, and HDR drifted away into the far reaches of photographic memory.

Or did it?

HDRs Evolution To A Powerful Tool

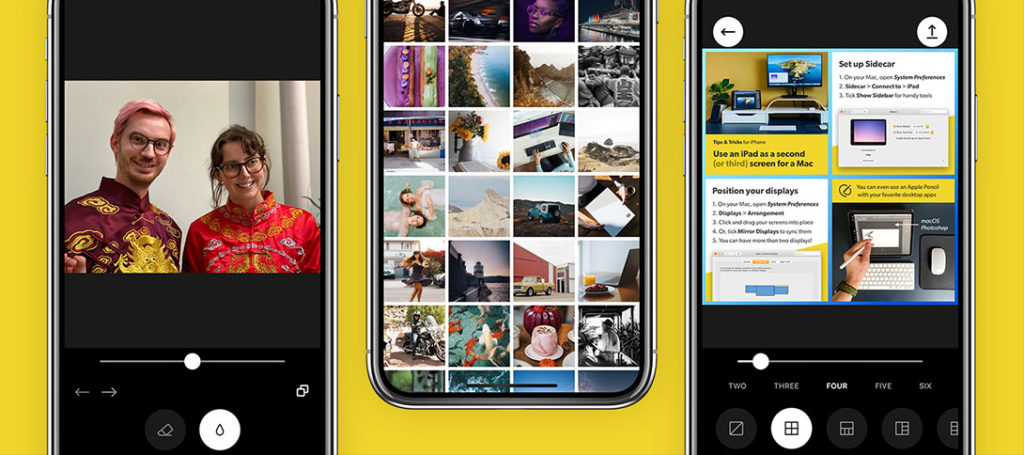

HDR never went away. It’s always been a technique, which when used well, allows the photographer to create beautiful images that a single image just could not cope with. As photographic editing software such as Lightroom evolved, HDR tools were incorporated to make producing one much easier.

However, if there is one addition to the HDR technique that allowed it to become such a modern powerful tool, it was the ability to merge RAW files. Before this, HDR was done mostly by merging JPG files, or sometimes TIFFs. However, as you will know the dynamic range of a JPG is significantly reduced compared to a RAW.

So although we would still improve our dynamic range by merging JPGs, it was nowhere near its full potential.

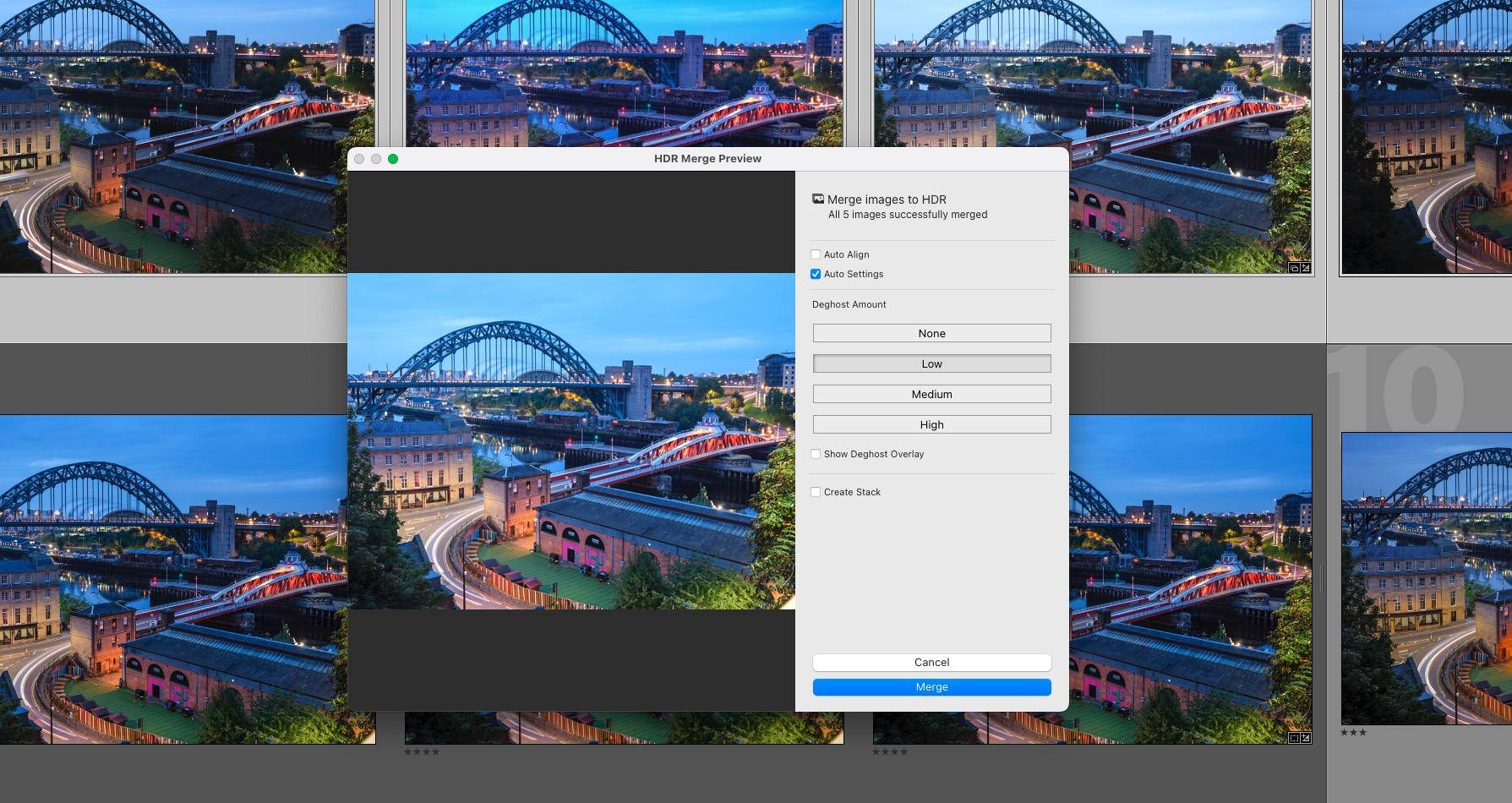

When Adobe introduced RAW HDR merge to Lightroom, it changed everything. Now we could merge multiple RAWs into one large DNG (Adobe’s proprietary RAW file). With that came all the benefits of shooting RAW. Fine control over the white balance, the big increase in editability of files, and of course an even more enhanced dynamic range.

Now, we photographers can shoot HDR images the way they are meant to be, allowing us to see a scene in a similar way to our own eyes, regardless of the contrast in that scene. We can be subtle with the HDR, lift shadows a touch, drop a little definition into the sky all whilst maintaining a natural-looking image.

It is a tool that has very much matured.

It’s Still Not Perfect

Despite, for the most part, garish HDR having been banished to the trashcan of history, it is still not without its problems. Movement in shots is one major issue. Whilst modern software will try to negate and remove obvious movement, smaller details such as leaves can be an issue. For example, if trying to shoot an autumn forest scene with a very bright sky you might go the HDR route.

However, if there is a relatively strong breeze blowing, the leaves will be in different positions for each shot, no matter how quickly you shoot the bracket. Even the most sophisticated HDR software can turn these leaves into a mushy mess. The same is true if there are multiple people in the bracket. You can end up with some very strange-looking apparitions.

Despite the limitations, HDR has become a powerful technique for photographers. Modern software, RAW files, and auto bracketing have combined to make sure that HDR is going to be around for quite a while.